Is it time to raise Social Security's retirement age?

The RetirementRevised newsletter delivers a deep dive into key news and trends about retirement and aging via email, from my perspective as one of the top journalists covering the field over the past 15 years. My aim is to provide a must-read weekly summary of developments in policy, research and markets for retirement and aging professionals – and for anyone else with a deep interest in the field.

I publish the newsletter 48 times annually on Friday afternoons (and sometimes on Saturday).

Read on below for a recent sample edition - to subscribe, click the icon below. No obligation, and feel free to cancel at any time!

Is it time to raise Social Security’s retirement age?

The idea of raising the Social Security retirement age crops up often as a way to fix the long-term financial challenges facing the program. On its face, this sounds reasonable to many people - after all we’re all living longer, so why not make people wait a bit longer for benefits?

It’s a polarizing idea and debate about it often deteriorates quickly into partisanship. But a new report on this question from the Urban Institute takes an even-handed approach, examining the arguments and pro and con.

The paper, titled “Is it Time to Raise the Social Security Retirement Age,” was researched and written by Richard Johnson, an economist and senior fellow at the think tank. Rich is one of the country’s top experts on the aging of the workforce and retirement programs, and he has been a trusted resource for me since I began covering retirement a decade ago.

When Social Security was created in 1935, benefits began at age 65. Starting in 1956 for women, and in 1961 for men, retirees could claim benefits as soon as age 62, but monthly benefits were reduced permanently depending on how early they filed. Meanwhile, the age when 100 percent of earned benefits are paid - the full retirement age (FRA) - began to rise gradually under reforms legislated in 1983. The FRA is gradually increasing to age 67 for workers born in 1960 or later; for example, workers born between 1943 and 1954 reach their FRA at age 66; for people born in 1955 the FRA will be 66 and two months.

Social Security faces a long-run financial imbalance - the program is now spending more than it takes in annually in payroll taxes. The Social Security trustees project that the program will be unable to pay full benefits beginning in 2034; unless Congress takes action, benefits would be slashed across-the-board by about 25 percent.

Congress has three options for avoiding this dire outcome. It could raise revenue by increasing the payroll tax and increasing the share of wages subject to the tax. A second option is to cut benefits by reducing cost-of-living adjustments or through other benefit formula changes. The third option is raising retirement ages - effectively reducing the number of years, on average, when benefits are received. That could close roughly 27 percent of the long-term shortfall, Johnson calculates.

Rising longevity is one argument often made in favor of that last reform. Americans live several years longer, on average, than they did when the early retirement age was introduced, and longevity is forecast to rise 2.8 years by 2050. “The program’s costs will rise as people live longer,” Johnson told me in an interview. “Is there a certain number of years of life we want to finance in retirement that we maintain by shifting that period later?”

The retirement age debate usually focuses on the FRA, but Johnson focuses here mainly on whether the early retirement age should be increased. “If we want to raise the FRA, we also would want to raise the early age,” he said. “If the gap between the two gets too large, it would create inequities.”

Here is what that means. Johnson calculates that filing at 62 currently translates into a 30 percent monthly benefit cut compared with filing at the FRA; if the FRA were increased to 69 without lifting the early age, that early-filing reduction would jump to a whopping 40 percent. “That might be a wash in lifetime benefits, depending on how long you live,” he said. “But the larger point for most retirees is, you pay your bills on a monthly basis.”

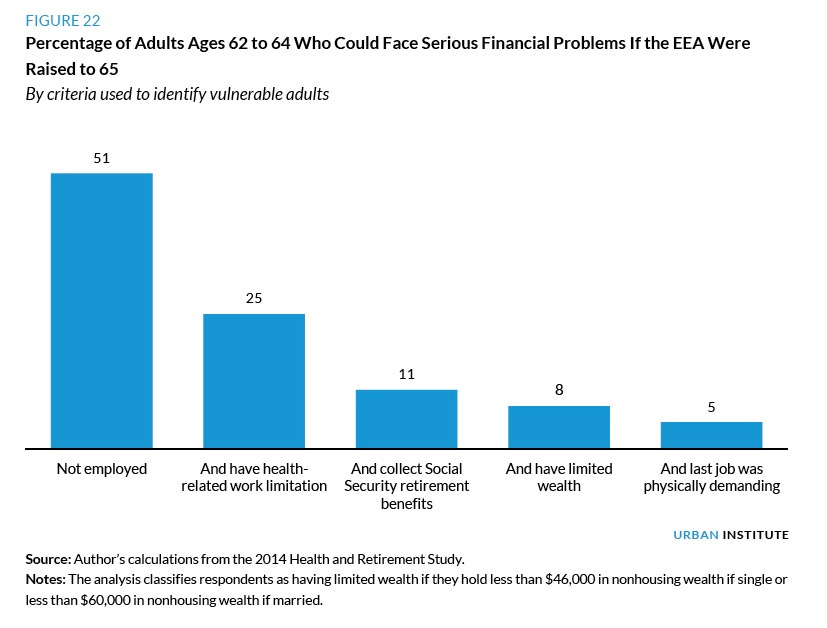

But increasing the early filing age would create hardships for many workers. If it were raised to age 65, Johnson estimates that 25 percent of workers aged 62 to 64 would face serious financial problems; that represents the share that is not working and has a health-related work limitation.

These workers are more likely to have health problems in their early sixties that limit their work ability, Johnson concludes, and many will not be able to pass the strict medical and functional screens of Social Security Disability Insurance. He also cites ongoing reluctance among employers to hire older workers, and the fact that the recent gains in life expectancy have gone mainly to people with more education and income.

Here’s how the distribution of that pain looks displayed as a chart - read it as a series of “and ands” - that is, 51 percent of this group that is unemployed will experience hardships; so will 25 percent of those who are unemployed and have a health-related work limitation. Etc.

What kind of policy changes could be made to buffer the most vulnerable people from higher retirement ages? Johnson suggests exempting workers in physically-demanding occupations; making the Social Security benefit formula more progressive than it already is to favor low-earners even more; expanding employment services and training and expanding unemployment insurance for older workers.

But he concedes all of these would be challenging policies to achieve from a political standpoint. “Most programs for desperate people don’t get a lot of funding, so the prospects are not great,” he said. “There is a real risk that we could raise the early Social Security filing age and not offer enough protections to the people most at risk.”

Johnson doesn’t say so out loud, but the unmistakable conclusion of his study is that boosting retirement ages further would be terrible policy. His paper is available for downloading here, should you want to dig into the details.

When couples do - or don’t - retire at the same time

Married couples really need to step up their game when it comes to discussing their retirement plans.

A recent survey by Fidelity Investments found that 43 percent of married couples disagreed about the age when they will retire, and 54 percent don't know how much they will need to save for retirement (including 46 percent of people who already are retired or getting close).

These data points come as no surprise to Kathleen Burns Kingsbury, an expert on wealth and psychology and author of How to Give Financial Advice to Couples: Essential Skills for Balancing High-Net-Worth Clients' Needs.

"It's similar to a lot of other money conversations that we tend to put off," she says. "Either we think it will lead to a fight or that we'll have plenty of time to talk about later."

But the couples disconnect also reflects the reality of retirement today--the timing is much more fluid, with couples often staggering their timing for financial or career reasons. Indeed, recent research concludes that it's rare for couples to retire at the same time these days. Learn more at Morningstar.com.

Getting the most from a Health Savings Account

A growing number of workers have health savings accounts (HSAs) associated with the health insurance provided by employers. These accounts have terrific tax advantages, and can help build resources to cover health expenditures in retirement. But not all HSAs are equal - investment options and fees can vary widely. As Elizabeth Olson explains in this New York Times Retiring column, some comparison shopping can help minimize fees and maximize savings.

If you have health insurance through your employer, your HSA usually is selected for you, and your employer probably pays maintenance fees. But if you’re buying insurance on your own — or if you don’t like the investment options available in the account your employer offers — you can choose another account provider.

Olson’s column incorporates recent Morningstar research surveying the HSA landscape. That report concludes that HSA plans are improving their quality of investments and menu designs, but no plan earns positive marks across the board for use as a spending or investing vehicle.

Correction

Last week’s newsletter stated incorrectly that you cannot pair traditional Medicare with a Medigap supplemental plan. I had that upside down - you cannot pair Medicare Advantage with Medigap. Advantage plans cap out-of-pocket expenses much as a Medigap plan would do. If you have traditional Medicare, consider adding Medigap.