Retirement 10 years after the financial crisis: How are we doing?

This is a sample edition of the subscription RetirementRevised.com newsletter. I hope you’ll consider subscribing - learn more about the newsletter and sign up here!

With best regards,

Mark Miller

Ten years after onset of Great Recession, how are U.S. retirees doing?

I’ve been covering retirement for more than a decade now, and I was fairly new on the beat when the financial crisis and Great Recession began. My first book, The Hard Times Guide to Retirement Security, examined the “what now?” questions that millions of Americans were asking about their future as they lost homes and jobs.

This month marks 10 years since one of the most dramatic events of the financial crisis - the collapse of the Lehman Brothers investment bank. A decade later, it’s striking for me to consider how far we have come in some ways. The economy has recovered by most standard measures - the stock market is making record highs, unemployment is at a 50-year low point, gross domestic product is rising sharply and consumer confidence is at an 18-year high.

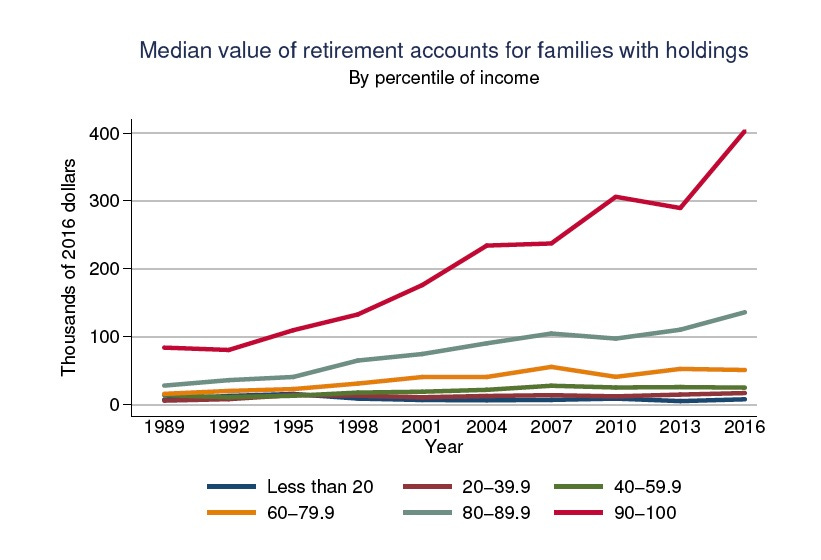

But the picture remains very mixed on retirement security. Ten years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, retirement security in the United States is a tale of two realities. For the affluent, retirement is looking pretty good, but many lower- and middle-class households continue to struggle, and face a very uncertain retirement.

Let’s run a few numbers on two of the most important elements of retirement security: housing and retirement saving.

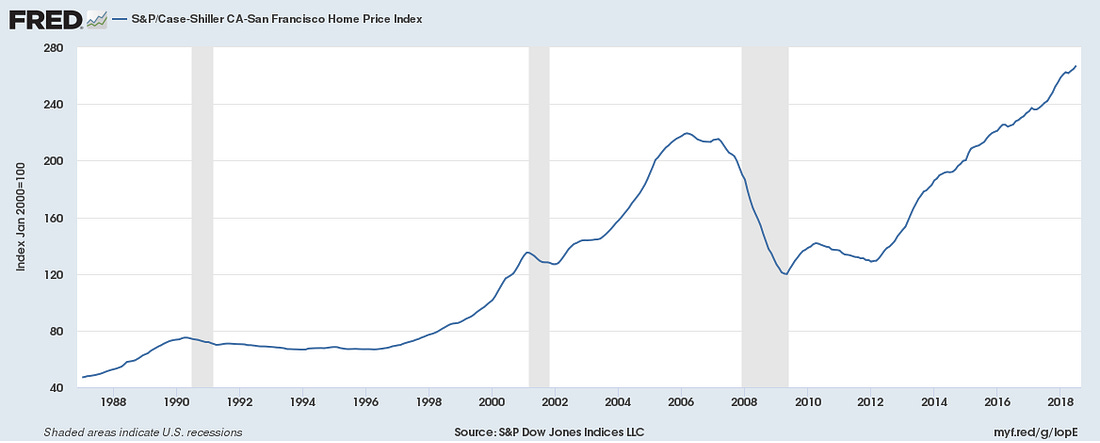

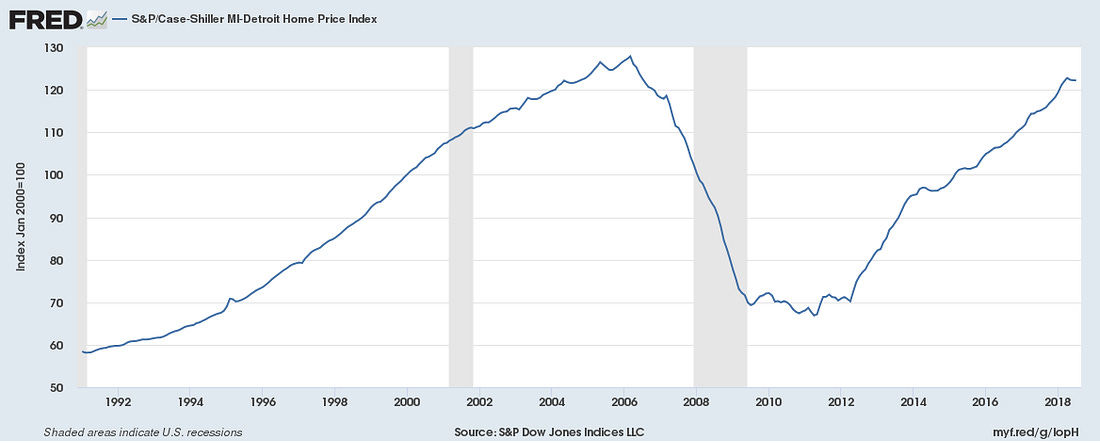

Housing: In August, real housing prices (adjusted for non-housing inflation) remained nine percent below where they were in 2006, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (JCHS). Of course, that is not true everywhere; if you live in a super-heated housing market such as San Francisco you’re seeing something very different than in Detroit, for example. Here’s what the recovery has looked like in those two cities, according to the widely-followed Case-Shiller index

The foreclosure crisis following the bubble’s collapse had a relatively small impact on retired households (aged 65 or older) - home ownership fell at the smallest rate for any age group - down from 81 percent in 2004 to 79 percent in 2017, JCHS data shows. But among households aged 55 to 64, the home ownership rate fell from 82 percent in 2004 to 75 percent in 2017. That points to a large group of people who will retire without home equity.

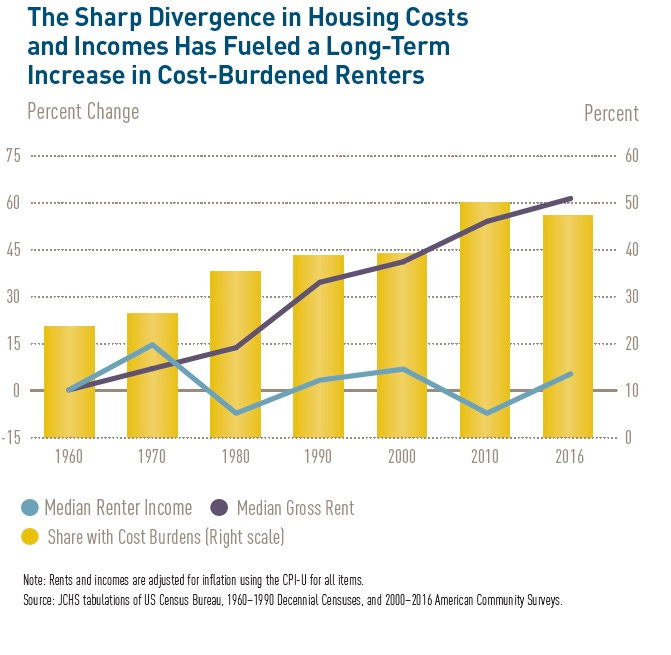

Seniors who do not own homes also will be subject to the volatility of rental costs, which have spiked in recent years and show no signs of slowing down. Nearly one-third of all households were cost-burdened in 2016, JCHS reports, meaning they paid more than 30 percent of their incomes for housing; among renters, 47 percent were cost-burdened.

Retirement saving: The data on retirement saving tells a story of rising economic inequality. First, consider that the stock market has rocketed ahead more than fourfold since March 9, 2009, when the S&P 500 bottomed out at 676.53. Here’s how it looks through late Friday afternoon this week from that bottom:

Meanwhile, very little progress has been made in making retirement accounts more available to workers since the recession. Fifty-two percent of families had access to retirement accounts in 2016 - down from 53 percent in 2007, according to the SCF.

And the coverage story is worse among single people, minorities and less educated workers. For example, 35 percent of single workers without children had access to retirement accounts in 2016, unchanged from 2007. And 92 percent of families in the top 10 percent of income had access in 2016, compared with just 11 percent of the lowest-income families, SCF data shows.

In my Reuters column this week, I checked in with economic and policy experts from across the political spectrum for their take on where retirement security stands ten years after Lehman. From the left, I heard calls for improved access to retirement accounts, expansion of Social Security and restoration of defined benefit pensions. Researchers representing the financial services industry (let’s call them the center and center-right) point to numbers indicating that things are going better than some of the numbers I just showed you would suggest.

A much-discussed Census Bureau study published last year suggested that retiree income in 2012 was 30 percent higher than previously reported. And several studies have found that surprisingly few retirees are drawing down their nest eggs - instead, they seem to be hanging on to savings to meet emergency needs, and are living on whatever annuity-style income they have from Social Security and pensions.

The ICI - which represents the mutual fund industry - likes to change the subject a bit on this question - its economists point to Social Security when asked about the lower 401(k) coverage numbers for lower-income workers. ICI notes - correctly - that Social Security replaces a higher percentage of preretirement income for less affluent households, and that the system is designed to encourage more affluent households to save, since they will not receive as income (relatively) from Social Security. But I think it’s a stretch to refer to this as a “design” feature. There is no evidence that the founders of Social Security envisioned a huge private pension system back in the 1930s, as Nancy Altman makes clear in her recent book, The Truth About Social Security.

What’s more, there is good reason to worry if we’re relying on Social Security and defined benefit pensions to underpin lower-income households. DB pensions are disappearing in the private sector, and the value of Social Security is falling due to the reforms enacted in 1983. That is an argument for expanding Social Security - something I favor.

When (if?) the reform discussion gets going, we will hear proposals to target expansion to lower-income households. But I’m wary of those arguments - let’s remember Social Security benefits already have been cut across the board for GenXers and millenials under the 1983 reforms, and they will need help in retirement. And targeted expansion puts us on a slippery slope toward redefining Social Security as a means-tested program, rather than an earned retirement benefit. That should be resisted.

Don’t let this happen to you

The Securities & Exchange Commission accused a former Wells Fargo broker of stealing money from the accounts of elderly clients - some of whom suffered Alzheimer's - to make up for shortfalls with other customers.

Cognitive decline leaves older people vulnerable to financial fraud and abuse. Combine that with several other trends and you have a perfect storm of financial risk: the increasing reliance on self-managed retirement income through individual savings and 401(k) accounts, growing use of debt by older households, and more problems with computer security and hacking.

Perhaps most worrisome, confidence in our ability to make sound financial decisions does not decline commensurate with cognitive loss. One study found quite the opposite: confidence in financial decision-making ability increases with age.

Learn more about how to protect yourself here.

Medicare to extend deadline for reversal of late enrollment penalties

People who sign up for Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace exchange health policies before turning age 65 can easily make the mistake of sticking with those plans past age 65, when - by law - they need to switch to Medicare. That results in costly lifetime late-enrollment penalties on your Medicare premiums.

Confusion about the transition from ACA plans to Medicare has been so widespread that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) opened up a window for a limited time last year allowing people caught in the switches to apply for relief from the penalties. The deadline for that application was the end of September this year, as I reported in June. Now, the deadline has been extended for an additional year, according to the Medicare Rights Center:

Great news! @CMSGov will be extending time-limited equitable relief for another 12 months for people with #Medicare who need more time to understand their options. See here for why this decision matters and why we are grateful to CMS for listening! https://t.co/0zOAZhNmdC

September 28, 2018SEC wants to liberalize rules for risky investments

The Securities and Exchange Commission aims to open up private placements to a larger share of investors. But a Wall Street Journal investigation notes that this type of investing in private companies can be very high-risk and more opaque than the public stock market, and a draw for scam artists:

Tens of billions of dollars a year of private stakes in companies are now being sold by securities firms with an unusually high number of brokers with three or more investor complaints or other red flags on their records, a recent analysis by the Journal found.

Learn more here (subscription required).

Should states regulate financial planners? The planners can’t agree

The fiduciary rule is dead and concerns are mounting that the Securities & Exchange Commission’s replacement for it will be weak and confusing for consumers. Some states are moving to create and enforce their own requirements that financial advisers put the best interest of clients first.

But now, it appears that two key planning groups may be staking out opposite positions on this. The Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards announced this week that it will oppose fiduciary regulation by states arguing that it would place unreasonable burdens on advisers who work across state lines. Meanwhile, the Financial Planning Association is leaving open the door to state regulation, as Michael Kitces notes here.

Working while receiving Social Security benefits: How it works

It is possible to work and receive Social Security retirement or survivors benefits. But if you do this before reaching your full retirement age (FRA), your benefits may be reduced, at least temporarily. Jim Blankenship, a financial planner and Social Security expert, explains.

A Medicare reminder

Medicare fall enrollment starts on October 15th, and runs through December 7th. More on that next week.