The coming long-term care collision

Demand and costs for care are rising at the same time that a labor shortage threatens to worsen. How should you plan for a possible long-term care need?

How to manage for the possibility that you’ll need expensive long-term care as you age? This has long been one of the toughest challenges in retirement planning and policy circles.

Will you need care? Probably—but the intensity and duration of need are impossible to predict. Who will provide care - a family member or a paid professional? How will you pay for care?

Insurance is one logical solution for an unknown, potentially expensive risk like this. But in this case, not so much. Private long-term care insurance is expensive, complicated and unpopular. Medicare doesn’t pay for LTC (although many think it does). Medicaid is the main funder of care in the U.S., but you need to be impoverished to qualify - and the program is under attack by the Trump administration and their MAGA allies in Congress.

This seems like a good moment to reassess the long-term care landscape, which I’ve done in my new “Retiring” column for The New York Times (gift link here). In this edition of the newsletter, I offer a summary of the Times column, and some additional points that wound up on the cutting room floor due to space constraints.

First, LTC is experiencing a perfect storm of market economics. On the demand side of the equation is an aging population. In 2026, the oldest baby boomers will start turning 80, an age when the odds of needing care grow. The U.S. Census Bureau forecasts that the number of people 85 and older will nearly double by 2035 (to 11.8 million people) and nearly triple by 2060 (to 19 million).

At the same time, the care industry has a shortage of workers that is driven partly by low wages. The median hourly wage for all direct care workers was $16.72 in 2023 — lower than the wage for all other jobs with similar or low entry-level requirements.

Experts fear that shortage will be exacerbated by the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown. Immigrants make up 28 percent of the long-term care work force — a figure that has been rising in recent years, according to KFF, a health research group.

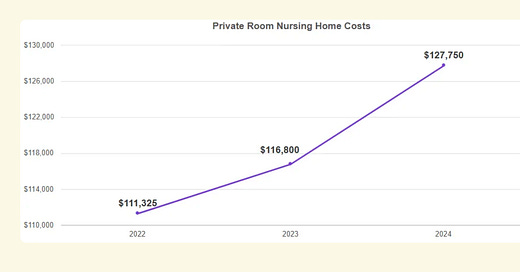

The price of some long-term care services in 2024 rose as much as 10 percent, according to a study by CareScout — more than triple the 2.9 percent general rate of inflation that year.

Much of your medical care in retirement will be covered by Medicare. Long-term care refers to help with daily living for people who are frail or disabled — bathing, dressing, using the toilet, preparing meals, shopping, walking and taking medications.

Most Americans have misconceptions about how they might pay for those needs, or haven’t planned for them at all. KFF polling shows that 23 percent of all adults — and 45 percent of those age 65 or older — incorrectly believe that Medicare will cover their time in a nursing home if they have a long-term illness or disability. Fewer than half of adults said they’ve talked seriously with loved ones about how they would obtain or pay for long-term care. And among near-retirement individuals, just 28 percent say they have set aside money for it.

How should you think about the risk of needing care, what it will cost and how to pay for it? The answers might include long-term care insurance, savings, finding ways to optimize your guaranteed retirement income, Medicaid or reliance on a family member.

Addendum to the NYT column

If you’ve read the column and would like to know more, here are a few additional points to consider.

Cost of care: The national average prices for various types of LTC are useful as trend indictators. But when you’re trying to estimate what care might cost, consider what type of care you might need, and where you might get it. The Carescout survey shows considerable variation in the cost of care by region; you can research and compare costs here.

LTC insurance: If you want to buy private LTC insurance, experts recommend “cash indemnity” rather than reimbursement policies. With a reimbursement policy, you hire a care provider through a licensed home care or health care agency, and you must submit bills every month. Cash indemnity plans will pay anyone you choose. “It's similar to a disability policy,” says Brian Gordon, an insurance broker specializing in LTCI. “The insurer will cut a check each month to pay whoever you want to provide care.” (That is, after any elimination or waiting period is met.)

Medical underwriting: It’s best to buy LTC insurance in your 50s or early 60s. Insurers require that you pass a medical exam (“medical underwriting”), and won’t write policies for people who already suffer some chronic conditions, including Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson's, debilitating arthritis, certain stages of cancer - even people who use a cane or walker. Some medical conditions might require an adjustment period (three months to a year) after treatment or physical therapy before qualifying.

The workforce, immigration and quality of care: David Grabowski at the Harvard Medical School is very worried about the impact of Trump’s immigration crackdown on the LTC labor force. “Everything that we found in our research suggests that when you have an influx of immigrants to an area, you have more individuals working in long term care settings, and more workers, not surprisingly, is associated with higher levels of quality,” he told me. “Long term care is incredibly labor intensive -this isn't a high technology sector. This is about assisting individuals with bathing, dressing, toileting and walking. These kinds of tasks involve hands on care, and the more hands that are available to do that care, the better the outcomes.” He adds that immigrant workers are not crowding out native-born workers. “It’s not that that anybody's job is being being stolen - long term care providers really struggle to find staff members, and foreign born workers have been a big part of the answer. They are a major part of the backbone of our long term care system.”

The labor shortage fallacy: Economists will tell you that employer complaints about “labor shortages” usually reflect not an actual lack of willing workers, but rather a refusal to pay wages and provide conditions that attract them. In other words, the issue is not that “no one wants to work,” but that people don’t want to work for poor pay or with bad working conditions. If demand for labor exceeds supply, wages should rise and working conditions improve. But that often doesn’t always apply in the world of long-term care, largely due to Medicaid reimbursement rates, which generally don’t keep up with rising costs or market wage rates. These rates are set by states, and they vary, notes Grabowki. “States that have minimum staffing standards and pay more have been able to increase staffing,” he says. “But we need to improve wages and working conditions and benefits and everything about this job, and increase the number of individuals who want to do this work.”

Why don’t more people plan for a possible LTC risk? Many people confuse health care and long-term care - and that might explain why so many people think (incorrectly) that Medicare will cover it. Another reason is a form of denial, according to Gal Wettstein, a researcher at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. “The research shows that people are pretty pessimistic about their longevity, at least in these kind of early retirement ages or late career stages. People in their 50s and 60s tend to be unreasonably pessimistic about how long they're going to live, and so if they don't think they're going to make it to an advanced age, then they might not worry about long term care, which is usually a problem in advanced age.”

The House bill slashes Medicaid, and threatens Medicare

How might the LTC landscape deteriorate further? The U.S. House of Representatives had the answer this week, approving the brutal Medicaid cuts that I wrote about earlier this week and sending them on to the Senate.

The legislation includes drastic cuts to Medicaid that will harm Medicare beneficiaries and all older adults and people with disabilities who receive long-term care in nursing facilities and at home. It also mandates harsh work requirements for adults up to age 65, which in reality function as cuts to Medicaid by another name. Many Medicaid beneficiaries who will be kicked off of Medicaid due to the red tape of work requirements are people with disabilities, older adults and their caregivers.

The legislation also delays (by ten years) a new rule setting standards for nursing home staffing that would have improved care for residents and supported nursing home workers. Research estimated that the staffing rule would save 13,000 residents’ lives each year. Postponement will jeopardize the health, safety, and lives of nursing home residents.

Here’s a quick 10-question quiz that nicely summarizes the horrors contained in this legislation, via Robert Reich:

1. Does the House’s “one big beautiful bill” cut Medicare? (Answer: Yes, by an estimated $500 billion.)

2. Because the bill cuts Medicaid, how many Americans are expected to lose Medicaid coverage? (At least 8.6 million.)

3. Will the tax cut in the bill benefit the rich, the poor, or everyone? (Overwhelmingly, the rich.)

4. How much will the top 0.1 percent of earners stand to gain from it? (Nearly $390,000 per year.)

5. If you figure in the benefit cuts and the tax cuts, will Americans making between about $17,000 and $51,000 gain or lose? (They’ll lose about $700 a year.)

6. How about Americans with incomes less than $17,000? (They’ll lose more than $1,000 per year on average.)

7. How much will the bill add to the federal debt? ($3.8 trillion over 10 years.)

8. Who will pay the interest on this extra debt? (All of us, in both our tax payments and higher interest rates for mortgages, car loans, and all other longer-term borrowing.)

9. Who collects this interest? (People who lend to the U.S. government, 70 percent of whom are American and most of whom are wealthy.)

10. Bonus question: Is the $400 million airplane from Qatar a gift to the United States for every future president to use, or a gift to Trump for his own personal use? (It’s a personal gift, because he’ll get to use it after he leaves the presidency.)

A caveat on that $500 billion Medicare cut: it’s not certain this will happen. This refers to a potential reductions in spending from 2026 and 2034. KFF explains:

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the reconciliation bill reported out of the House Budget Committee would increase the deficit compared to current law by at least $2.3 trillion. If enacted into law in its current form, and Congress takes no further action, that increase in the deficit would trigger mandatory cuts, also known as sequestration, under the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010. Unlike Social Security and programs for low-income people, Medicare is not exempt from these cuts.

These cuts would be imposed on health care providers and Medicare Advantage plans - if they happen at all. It would be fair to expect fierce lobbying from these folks for an exemption.

KFF also offers this table summarizing the Medicaid changes contained in the House bill.

The proposed legislation now moves to the Senate, which is likely to reshape it in ways that are difficult to predict.

What I’m reading

UnitedHealth secretly paid nursing homes to reduce hospital transfers . . . The bond market is waking up to the fiscal mess in Washington . . . Bond investors to Washington: We’ll make you pay.